President Joe Biden will forgo the usual video call for his first in-person meeting with a foreign leader on Friday, when Japan’s Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, who is fully vaccinated, meets Biden at the White House.

A new president’s first meeting slot with a foreign leader is normally reserved for top allies. Biden’s predecessor President Donald Trump held his first get-together with British Prime Minister Theresa May (although he met former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe for an informal 90-minute conversation at Trump Tower in New York before his inauguration).

Experts say that Biden’s choice to meet Suga before other world leaders shows that he sees some of the most important issues facing his administration— including how to deal with China—as being located in the Indo-Pacific region.

“Biden‘s decision to hold his first in-person summit with Suga sends a strong signal about Japan’s importance as a partner in dealing with some of the biggest challenges facing the United States and the importance of the Indo-Pacific region in Biden‘s foreign policy,” says Kristi Govella, an assistant professor of Asian Studies at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

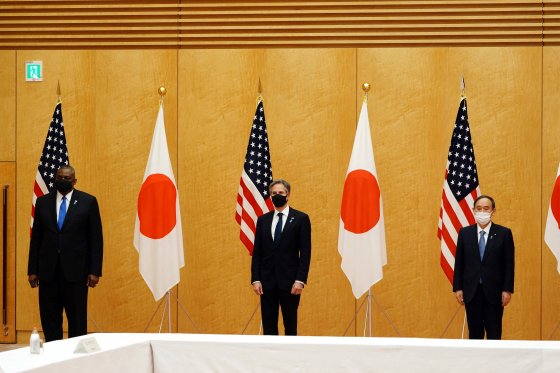

Countering Trump’s “America first” isolationism, Biden has made mending ties with allies a priority since his inauguration. On Mar. 12, Biden joined a virtual summit with the leaders of Australia, Japan and India—the first summit for the leaders of the so-called “Quad” strategic bloc. Days later, Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin traveled to Japan and South Korea on the Biden administration’s first Cabinet-level trip abroad, in meetings that have been dubbed the 2-plus-2.

“Biden wants to revive U.S. networks of influence that were shattered by Trump’s erratic gambits in diplomacy,” Jeffrey Kingston, the director of Asian Studies at Temple University’s Tokyo campus, tells TIME. “He is announcing the U.S. is back in Asia and will emphasize multilateralism.”

The U.S. relationship with China doesn’t look set to improve significantly in the near-term, though. Relations sank to a decades-low nadir during the Trump administration, and high-level meetings between China and the U.S. in Alaska last month descended into finger-pointing and squabbling. The U.S. excoriated China for its threats against Taiwan and its clampdowns in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, while a top Chinese diplomat lectured the Americans on race issues and other U.S. failings.

Tensions with China have given renewed importance to Washington’s alliance with Tokyo. Here’s what to expect from the summit.

What’s on the agenda for Biden and Suga?

Biden, 78, and Suga, 72, are expected to cover a wide variety of topics including climate change, COVID-19, economic ties, technology and security issues. But how to work together to deal with China, which the U.S. finds itself increasingly at odds with, is likely to be an overarching theme.

“In terms of the substantial importance of the meeting, I think everything is all about China,” Yoshikazu Kato, a research fellow at the Rakuten Securities Economic Research Institute in Tokyo, tells TIME.

China’s territorial claims in the East and South China Seas are an increasing point of tension between the U.S. and China and a major security concern for Japan. According to the Japanese broadcaster NHK World, Chinese vessels entered Japan’s territorial waters more than 10 times this year around disputed islands known as the Senkaku in Japan and the Diaoyu in China.

Taiwan is likely to be a main major topic of discussion. Tensions over the island, which China considers a breakaway province, have increased as China increases military activity in the area.

Biden may also seek to address a “growing frustration over differences in values diplomacy and Tokyo’s ambivalent commitment to human rights and democracy,” says Kingston. “Japan supports human rights and democracy but is not prepared to risk anything in support of those values.”

The U.S. and several other countries have slapped Chinese officials with sanctions over eroding political freedoms in Hong Kong and the treatment of the Uighur ethnic minority in China’s northwest Xinjiang region, but Japan has not followed suit. China’s Foreign Minister warned Japan during a phone call on Apr. 5 against imposing punitive measures—and Japan is understandably cautious about antagonizing its largest trading partner.

Read More: Yoshihide Suga Is Japan’s New Prime Minister. Here’s What That Means for the U.S.

What does the Biden meeting mean for Suga and Japan?

A senior Japanese diplomat told TIME that the meeting is a chance for the countries to “demonstrate to the world that the free and open system works and democracy and rule of law count.”

The summit may also provide a chance for Suga, who was largely untested in foreign affairs before stepping into the role of Prime Minister, to show his mettle. He may hope that the meeting will boost his popularity at home, where he inherited a domestic agenda swamped by the coronavirus pandemic, the country’s biggest ever economic slump and the postponed Tokyo Olympics—set to go ahead in July despite opposition from a majority of the Japanese public. His approval rating has tumbled over public dissatisfaction with his government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, among other issues.

The visit offers Suga “a precious opportunity to boost his credentials as an adept steward of the U.S.-Japan alliance, at a time when domestic political support for his administration has dwindled,” says Mireya Solís, the director of the Center for East Asia Policy Studies at the Washington D.C.-headquartered think-tank the Brookings Institution.

Not all experts agree that the visit will pay off. With so many problems at home, “this is not good timing for Suga to visit the U.S.” says Kato. “Suga’s visit to the U.S. will not be that popular domestically, it will not contribute to improving his very low popularity.”

Read More: Yoshihide Suga Will Succeed Shinzo Abe as Prime Minister. What’s Next for Japan?

What will be the outcome of the Biden and Suga summit?

A joint statement is expected to be issued following the meeting, and the communique issued after last month’s 2-plus-2 meetings may provide some clues about what will be included. That statement “underscored the importance of peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait,” raised concerns about human rights in Xinjiang and Hong Kong and declared America’s “unwavering commitment” to come to Japan’s defense if need be.

Pundits say that it would be significant if the statement showed support for Taiwan. It has been decades since U.S. and Japanese leaders addressed the importance of Taiwan’s security in a joint missive.

But experts say that Japan’s economic dependence on China means that it can only push Beijing so far. Solís, of the Brookings Institution, says that Suga will “likely seek a strong message of deterrence towards China on the maritime domain but will tread carefully on sensitive issues—Taiwan, sanctions on human rights violations—to avoid a sharp deterioration of relations with Beijing.”

Suga is also expected to invite Biden to this summer’s Olympics in Tokyo, according to the Japanese media.

Whatever the outcome, the meeting marks a major shift in U.S. foreign policy from that of the Trump administration. “American allies in Asia will welcome increased engagement and predictability under the Biden administration,” says Govella, “though there is lingering concern about the willingness and ability of the U.S. to play a strong leadership role, given its tumultuous domestic situation.”

No comments:

Post a Comment