The power of family—in its love, pain and fierceness—is universal. It transcends time and borders, and connects people of every race, gender and sexuality. Yet throughout the world certain families are granted more respect—while others are placed under direct threat.

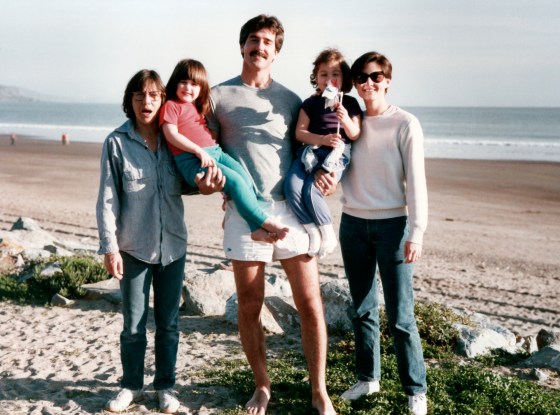

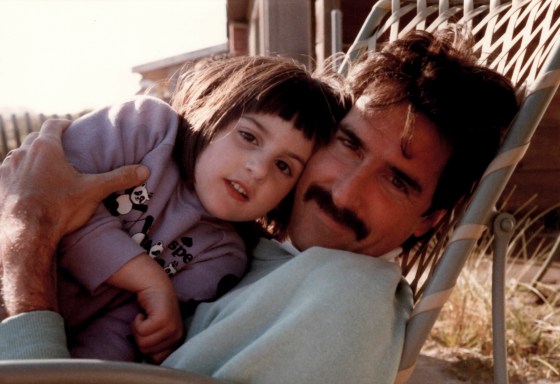

Such is the family at the heart of HBO’s new three-part documentary Nuclear Family, the first part of which airs on Sunday, Sept. 26. The series follows filmmaker Ry Russo-Young as she turns the camera on her own childhood, documenting how her two lesbian mothers, Robin Young and Sandy Russo, chose to form a queer family in the late ’70s and early 1980s in New York City—at a time when the concept was inconceivable to many within and outside of the queer community. Ry and her older sister Cade were born via sperm donors; two gay men that the girls grew up knowing. Their sense of safety was shattered in 1991, when Ry was 9 years old, and her donor, an attorney named Tom Steel, sued her mothers in New York for paternity and visitation rights. Nuclear Family follows the historic four-year legal battle over Ry, and the many sacrifices both parties made along the way.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

At its core, Nuclear Family is a powerful, intimate examination of a family fighting for its right to exist. Russo-Young explores the complexities and limitations of her own memory, probing her feelings toward a man who endangered her family—and risked creating legal precedent that would threaten thousands of LGBTQ families like hers—in the name of his love for her. It also highlights how far LGBTQ family rights have progressed in the years since the court battle—and how much further there is left to go.

“Families come in all different shapes and sizes, and mine was very clear. It was very intentional from the beginning. My moms knew what they wanted,” Russo-Young tells TIME. “And they’ve fought for that their entire lives.”

A transformative filmmaking process

Russo-Young has been trying to tell this story for 20 years. Versions have been told before, in print and television coverage both at the time of the trial and in its aftermath. But she says it was only after the birth of her second child, and her understanding of the “gravity of what it is to be a parent,” that she felt ready to finally take the plunge and tell it herself.

“The immensity of love that you feel for [your child] is so overwhelming,” she tells TIME. “I think it crystallized for me what my moms went through.”

A narrative filmmaker—whose past works include the young adult movies Before I Fall (2017) and The Sun Is Also A Star (2019)—Russo-Young originally thought she would create a narrative film about the legal battle. But those require heroes and villains, she says, and that is a dichotomy she intentionally wanted to avoid when laying out what occurred between Steel and her mothers. A documentary, on the other hand, can live in the shades of grey so often found in real life, and allow her to face long unanswered questions along the way.

“For the beginning, one of [my] goals was to allow myself… to hear the other side of the story,” she says. “I knew that it felt like it was scary to go there. And therefore I knew I wanted to walk through that door because I felt unresolved somehow, inside, emotionally with this whole morass in my life.”

The result is a complex exploration of familial love, which extends Steel an unexpected degree of empathy. A lesser film might simply condemn him—and in fact clips from media coverage in the immediate years after the suit show younger versions of Russo-Young doing just that. He undeniably threatened her family as she knew it: In order for Steel to be declared Russo-Young’s father by the court, her mother Sandy Russo would be defined as not a parent, since she was not biologically related to her daughter (Robin Young carried the pregnancy).

“Him suing made me feel like my world was completely rocked, my entire reality was being shattered,” Russo-Young shares. “And that’s what made me hate him.”

Yet she still goes to great lengths to examine his possible motivations, interviewing his friends, family and former legal team who make up for his notably absent voice, given his death in the late 1990s. She constructs an image of Steel that’s constantly shifting, morphing from a man motivated by selfishness, to a man acting out of desperation, to a man acting out of love, and back again. She probes her own recollections of him, intertwining verité footage of her time with him as a child with tapes he left for her to watch after his death. Ultimately, Russo-Young raises universal questions about the narratives every family tells itself, and the blurry line between where childhood memories end and the stories our parents told us begin.

The constraints of the American legal system

Nuclear Family also functions as a stark reminder of just how far LGBTQ rights have come in the decades since Steel first filed his lawsuit—showing how the limited imagination of the legal system when it comes to defining a family forced all parties into impossible situations.

When Russo and Young wanted to have kids in the early 1980s, not only was gay marriage decades away from being legalized, but most sperm banks would not serve same-sex couples, and same-sex couples had no legal protections.

“People didn’t know what to do with us both in the gay and lesbian community and outside of it,” Young recalls. “They were always trying to make us into anything but a real family.”

So when Steel filed his suit—one of the first of its kind in New York state—he put them in great danger. “We had absolutely no rights,” says Russo. “We had no tools to really defend ourselves and had to kind of invent and create the defense as the trial went forward.”

The legal battle took four years, eventually working up to the Appellate Division of the State Supreme Court.

“Gay families, my family, were so under the radar. It’s like we were a secret society… That we had gotten away with this miracle that was always sort of under threat.” Russo-Young says. “It felt like the law had caught up with us. We were having to contend with a system that we had always kind of avoided.”

In arguing for his right to be Russo-Young’s father, Steel and his legal team presented sexist and homophobic pseudo-science, including the now-defunct theory of “lesbian fusion”—a psychological theory from the 1980s that lesbians form overly close connections that are ultimately bad for the child. Steel’s team argued that children need a father, and it was not in the child’s best interest to be raised by two women instead of a woman and a man. He barred Russo from entering the courtroom, leading her to stand on a stool and look through the window of the door during the proceedings. “Tom took on the lawsuit knowing that the law he was going to have to use was an abomination,” says Nanci Clarence, Steel’s law partner, in the second episode. “But I think he felt he had no choice.”

“We were all traumatized in a kind of different way,” Russo tells TIME. “Robin and I just had to plow through and keep our hackles up. It was torture.”

“And the kids experienced it another way. They were frightened. And feeling betrayed,” she continues. “It was so immediate and so dangerous.”

In some ways Nuclear Family shows the family processing those events now, as Russo-Young keeps the camera rolling while she and her mothers discuss their conflicting views on Steel years after his death. While she may feel differently than she once did, her mothers do not. And that’s O.K. with all of them.

“[There’s] room in our hearts for Ry’s perception of Tom to change. I would say that’s the big change for us,” Young says. “She’s amazing, that she can transcend the muck and stuff that in a way we can’t get past.”

Read More: 9 Supreme Court Cases That Shaped LGBTQ Rights in America

The progress yet to be made

A 2018 study by the Williams Institute found that in 2016 an estimated 114,000 same-sex couples in the U.S. were raising children. Yet, to this day, the rights of those parents can vary widely depending on where they live.

It’s not enough in every state, for example, to be listed as a parent on a child’s birth certificate, even if you’re married. Instead, to be sure one’s rights are respected, advocates recommend LGBTQ parents legally adopt children they’re not biologically related to, or at least get a court to issue a judgment declaring them a parent, explains Amira Hasenbush, the founder and attorney at the LGBTQ family law firm All Family Legal.

In certain states sperm donors are still legally considered a parent unless the donation was done through a fertility clinic or via a medical procedure, adds Hasenbush. And certain LGBTQ families, particularly lower middle class families or families of color, choose to use a known donor instead given the high cost of a clinic and the lack of diversity in sperm banks, explains Angie Martell, the founder of the Michigan-based Iglesia Martell law firm, which practices LGBTQ family law. If that donor then chooses to claim paternity years down the line, as Steel did, in certain states it can be very difficult to legally fight back.

“Many states still bow down to the heteronormative notion that you need a mother and a father,” Martell explains. Yet repeated studies have shown same-sex parenting is not detrimental to the health and well-being of children.

In New York state, where Steel’s lawsuit was filed, protections for LGBTQ families have grown much stronger in the years since the legalization of gay marriage. In 2016, the New York Court of Appeals ruled in Brooke S.B. v. Elizabeth A.C.C. that if two parties enter into an agreement to conceive and raise a child together, or have gone through the process of raising a child, those parties will be recognized as parents—regardless of biology. In fact, in the 2018 case Christopher YY. v. Jessica ZZ., a male sperm donor who sued a lesbian couple for paternity of a child was squarely shot down by the court, citing Brooke S.B.. Courts in New York state have, depending on the facts of the case at hand, also begun recognizing families with three parents instead of two, slowly expanding their imagination of what a family can look like, says Eric Wrubel, a partner in the Warshaw Burstein law firm who practices LGBTQ family law and argued Brooke S.B. (Nuclear Family stresses the point that even if tri-parentage had been legally possible in 1991, it was not what Russo and Young wanted.)

Still, legal proceedings—including formal adoptions—are costly. Young and Russo had the means to fight back, but many LGBTQ families, particularly families of lower socioeconomic status, which are more likely to be families of color, do not. “There’s a schism, as we go further down the line, about privilege,” says Martell.

Russo-Young says the advancements that have been made when it comes to LGBTQ family rights, and the mainstream perception of LGBTQ families, became particularly evident to her as she made the film and combed over footage of media appearances she made as a teenager discussing the lawsuit.

“[In those clips] I’m still sort of trying to prove that I’m just like other kids,” she says. “And [that] I’m not kind of a freak actually, because that was still the public assumption.”

Yet despite all the media coverage at the time, Russo-Young says she’d never felt like the story was hers. Now, after creating Nuclear Family, she says she’s finally found her voice in it.

“This story has a lot of tentacles in terms of feelings and love for different people and alliances and loyalty,” she says. “But the most powerful relationship to me, at the end of the day, is the relationships [within] my nuclear family. Of my moms, [sister] and I.”

“The ability to survive that pain together, and to ultimately come out on the other side loving each other more than ever, that is the essence of what great families should do or aspire to do,” she continues. “And that’s the thing I really hope the movie does for people—make them think about their own family. Because everyone has a family of some kind.”

No comments:

Post a Comment